by Ray Bobb

Written Fall 2022, Published with kites August 2023

See also the kites Editorial Committee’s “Introducing Ray Bobb and the Urgent Questions Facing Native Politics in Canada Today,” as well as an interview with Ray Bobb commissioned by the kites Editorial Committee in the first half of 2023, all of which are being published alongside this contribution by Ray Bobb in kites #9.

Author’s Preface

Theory, Strategy and Tactics in the Native Movement (TST) is meant as a contribution to talk on the Native movement and its future. This contribution will be organized using the time-tested concepts of theory, strategy and tactics. The thought of TST comes from the author’s membership in two activist groups: the Native Alliance for Red Power from 1967 to 1970, and the Native Study Group from 1971 to 1975. TST also comes from more recent encouragement from and discussion with Joyce Mailhot, Cynthia Wright, Columpa Bobb, Geri Ambers, and Natalie Knight.

Ray Bobb is a member of the Seabird Island Indian band on the Fraser River and resides in Vancouver, BC. Ray’s Salish nation, when it existed, covered coastal and interior parts of what are now BC and the state of Washington. He was a member of activist groups known as the Native Alliance for Red Power, 1967-1970, and the Native Study Group, 1971-1975. Ray served in the Royal Canadian Navy before then and is a retired labourer with many relatives. He is sympathetic to the socialist project and loves the Native and working people of Canada.

Theory, Strategy & Tactics in the Native Movement

Theory considers the objective variables of history in their rising and falling trajectories of development. These trajectories can be projected into the future as probabilities. In the present, where the past turns into the future, conscious activity can be imparted as intervention into the developing equation of history to strengthen particular variables or accelerate their development. This conscious intervention is the movement’s long- and short-range plans. Strategy is based on and proceeds directly from theory. Tactics are short range plans directed by strategy and responding to changing political conditions. Depending on political conditions, tactical direction can, at times, seem to oppose strategic direction.

The politics of TST can be called revolutionary Indian nationalism (RIN). The theoretical basis of RIN is the concept of the Indian Nation as a modern nation. Modern nations in the world, except for India, China, and Japan, are the creation of European colonialism which, in several centuries, destroyed the tribal nations of the world by destroying the peoples themselves and their ways of life. Out of a great many tribal nations the European imperialists created a far fewer number of colonies or possessions from which each imperial power derived wealth exclusively for itself. These colonies became oppressed nations which eventually attained formal independence. These formally independent nations, under a new type of imperialism led by the US, became the neo-colonies or oppressed nations of the third world. Neo-colonies are ruled indirectly by imperialist powers through Native elites or puppet governments which, usually, are military dictatorships thinly disguised as democracies.

The Indian Nation as a nation of the exception was formed as an internal colony in 1867 when the settlers took power over the remaining British colonies in North America and created the Dominion of Canada, which is a settler-state and a small imperialist world power. The Indian Nation, so formulated, is meant to include the Inuit and Métis. This, however, is completely dependent on their decisions. The Native internal colony of Canada was and still is subject to direct colonial rule in and by Canada through the British North America Act, the Indian Act, and, what was then called the Department of Indian Affairs.

The existence of the Native internal colony, as a nation of the exception, limits the strategic possibilities, i.e., the means by which the internal colony can achieve national self-determination. Which is to say that the Native internal colony cannot, by itself, overcome the Canadian imperialist state. Strategy, so circumscribed, must proceed along the lines of an alliance between Native patriots and the progressive sector of the Canadian working class. When the working class seizes state power, national self-determination up to and including separation can be negotiated with the worker’s state. This strategy presupposes social revolution in Canada but, in RIN thought, the whole of the world capitalist social system must undergo a qualitative transformation or face a mass extinction event under the leadership of exploiters and oppressors. Such an event would be caused either by nuclear war, or by the failure of climatic or environmental sustainability. Moreover, the consciousness of the working classes in the imperialist countries will change and advance in the historic period now being embarked upon, i.e., the period of national liberation movements in the third world. This change in consciousness will be due in part to the fact that victorious national liberation struggles will weaken the imperialists, making it possible for workers in the imperialist countries to rise up.

The development of the theory of the Indian Nation from a modern nation to a nation of the exception, and to an internal colony, recognizes that an internal colony is a phenomenon of both the third world and the first world. On the one hand, the Native internal colony is a phenomenon of the third world in that, like the oppressed nations of the third world, it experiences a form of colonial domination. On the other hand, the Native internal colony is a phenomenon of the first world in that, geopolitically, it is located within an imperialist country and, demographically, its members are part of the working class of an imperialist country. The Native internal colony being a part of both the third and first worlds requires strategy with the dual, mutually-inclusive objectives of revolutionary integration and revolutionary sovereignty.

Revolutionary integration means that a part of the Native internal colony will struggle, not only for integration into Canada, but also for a Canada that is not exploitative or oppressive. Revolutionary sovereignty means that the other part of the Native internal colony will struggle not only for a sovereign nation, but also for a nation that is motivated not by profit and power, but by rationality and deep affection for others. Such a dual, mutually inclusive politics would forestall conflict as occurred between integrationists and nationalists in the time of the Black civil movement in the southern US. Movements with leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X would have empowered each other if acting in co-operation and as one revolutionary nationalist movement. One might say that, at the time, the integrationist movement did not have the revolutionary goals as proclaimed by the nationalist movement, but MLK was moving unmistakably to the left at the time of his assassination. Moreover, the end of racial segregation, sought after by the integrationists, was strategically a pro-alliance step and, probably, a precondition for social revolution in the US.

Ultimately, Indians resident in the oppressor nation could be allowed to hold dual citizenship in both Canada and the Indian Nation. Similarly, settlers and immigrants resident on Indian land could also be allowed to hold dual citizenship and full rights.

These aspects of the strategic alliance can be negotiated. With regard to settlers and immigrants being a part of the Indian Nation, keep in mind that nation and race are not synonymous. A racial struggle is one within a nation. A national struggle is one between nations. Right now the colonizer is in a position of such relative power that it can define who is or is not a member of the Indian Nation and it does so completely on considerations of race. Further, the colonizer seeks to continuously limit the definition of Indian by disqualifying the descendants and relations of Indian and non-Indian spouses. As the revolutionary nationalist movement grows, it will determine its own membership based on who wants to be a part, and what are the requirements, of the movement and the nation.

The tactics of the Native movement must, at this time, be focused on exposing, opposing, and reversing the Federal Government’s comprehensive treaty process and, paradoxically, defending the Indian Act. These tactics are considered so important by TST that tactics here will be related not to strategy but to contemporary theory in the form of the Federal Government’s Indian policy of forced assimilation as implemented in comprehensive treaties. If these tactics are, however, related to strategy it will be to exemplify how, at times, it is necessary for the movement to take one step back (in this case, to defend the Indian Act) in order to take two steps forward.

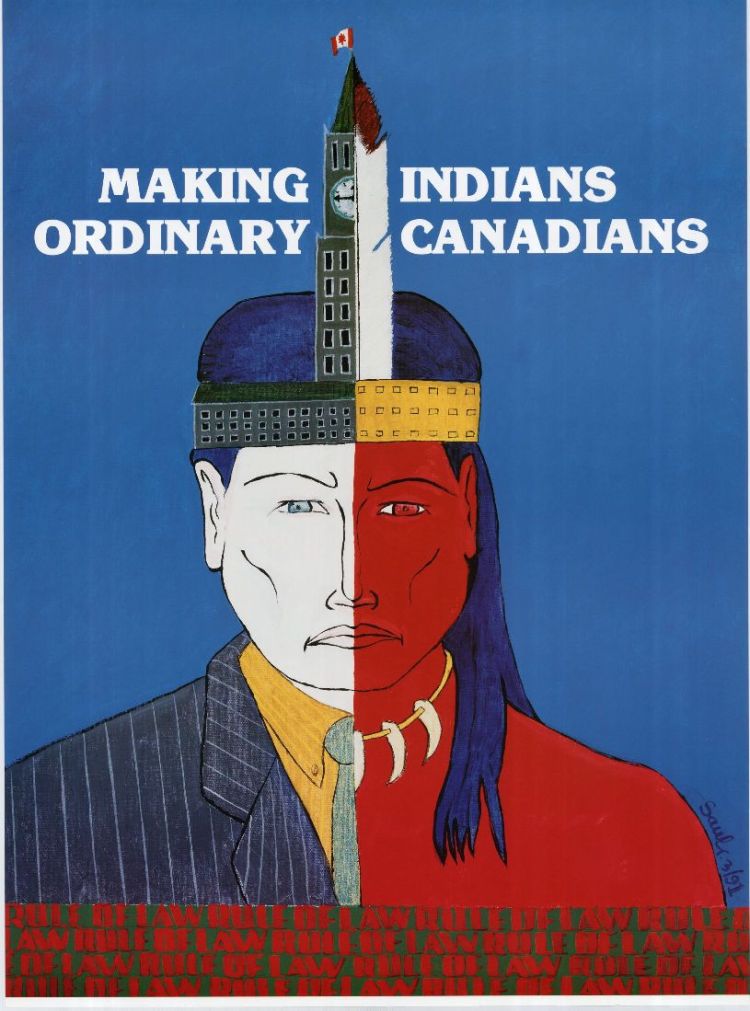

The comprehensive treaty process was created in the aftermath of the Federal Government’s 1969 “White Paper” policy on Indians,1 which proposed to forcibly assimilate Indians into Canada. The White Paper was met with a national uprising of Indians against the White Paper and its agenda. The Federal Government then changed its tactics. It withdrew the White Paper in 1971 and established an official source of government, applied for grants to carry out social reforms in the Native communities and to create a representative and captive Native leadership. In 1973, the Federal Government passed the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy as the basis of comprehensive treaty-making. For the purpose of making treaties, the Federal Government extended ostensible recognition of Indian bands as nations, i.e., First Nations, and proceeded to make coercive treaties with them. These treaties are fraudulent in that Indian bands are not bona fide nations. These treaties are also coercive on two levels. First, the comprehensive treaties contain a non-negotiable requirement which annuls the Indian Act in the area of treaty-making. Second, communities participating in the comprehensive treaty process are rewarded with money, land, and access to resources. Those communities not participating are left in poverty. The non-negotiable requirement in the comprehensive treaty process is the basis of the Federal Government’s Indian policy of forced assimilation. The non-negotiable requirement results in the denial of Indian nationality and rights including the retraction of all legislation pertaining to Indians and the dismantling of all institutions serving Indians. The comprehensive treaty process, over time, is meant to achieve the same objectives as the White Paper policy of 1969. The comprehensive treaty process uses the colonizer’s divide and conquer tactic by instituting tribalism. In the comprehensive treaties, bands and tribes are compelled to prove that, before contact, they occupied the land under negotiation. This causes friction between bands and between tribes. In war or politics, an Indian band faced with a national adversary can only find itself at a great loss.

The Federal Government denies the existence of the non-negotiable requirement in the comprehensive treaty process, but minimal research proves that the requirement exists. The Federal Government insists that it is the Indian bands that want to be rid of the Indian Act. However, it is passing strange that, united, the bands vehemently oppose the repeal of the Indian Act while, separately, the bands can be convinced to support the repeal.

The comprehensive treaty process was implemented first in northern Quebec (1975), and then went on to be implemented in the whole of the Canadian north. In the Canadian south the extinguishment process is now carrying on apace. On the BC mainland, for instance, only the Nisga’a and Tsawwassen bands have signed comprehensive treaties.2 This, despite the Federal Government having invested more than one billion dollars to facilitate the comprehensive treaty process.

In the US, in the 1950s, a similar wholesale attack on Indians took place. This attack was known not as an extinguishment policy aimed at doing away with nationality and rights recognized under the Indian Act (in the US there is no Indian Act as such), but as a termination policy aimed at doing away with Indian reservation land through privatization or through the purchase of Indian land by the Federal Government. The US termination policy was defeated and rolled back by Indian opposition and the courts.

The tactical reversal of the comprehensive treaty process refers not only to the mobilization of protest, but also to the utilization of the courts against the violation of a people’s rights inherent in the arbitrary denial of their nationality. The objective of reversing the comprehensive treaty process is to re-establish the legal and political condition of the people, i.e., their nationality and rights, prior to the implementation of the comprehensive treaty process.3 Additionally, a part of the successful reversal would entail financial compensation for those adversely affected.

Another tactical goal of the movement will be to develop, clearly, the difference between Indian national rights and prerogatives in relation to the rights of Indian bands or Indian territories. This, so that Indian bands can exercise their rights in regard to their evolving relationship to Canadian business and provincial or municipal governments without encroaching on national prerogatives. This encroachment does happen in the comprehensive treaty process. In such negotiations the invariant outcome for the Indian band is secession, i.e., the band secedes from the Indian Nation.

A further tactical objective of the movement should be for the emerging national leadership to end the captive or employee relationship that obtains between the Federal Government and Indian representatives regarding finance. Given that Indian claims to land, based on Aboriginal title, have not been legally settled, funds should accrue to Indian representatives, not by way of applied-for grants, but through the reception of a definite percentage of what is now the Federal Government’s intake from resource extraction and economic development.

In the search for a theoretical world view and a place for Indians in this world, TST posits the Indian Nation as a modern nation, as a nation of the exception, and as an internal colony. In the consequent search for a way forward TST arrives at a strategy of alliance with two, mutually inclusive, directions: dual citizenship in two friendly nations, and tactics of defense. Hopefully, these ideas can play a positive role in a reconciliation that finds Indians and Canadian workers marching shoulder to shoulder toward national liberation and the emancipation of labour.

1 kites footnote: Formally known at the time as the “Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy.”

2 kites footnote: There are actually four comprehensive treaties (also called modern treaties) in place in BC, not two. However, the most recent treaties are less known or discussed and it is widely thought that only two modern treaties have been negotiated in BC. The four treaties are: Nisga’a Final Agreement, effective in 2000 and negotiated outside of the BC Treaty Commission Process while adopting a similar framework, Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement, effective in 2009, Maa-nulth First Nations Final Agreement, effective in 2011 and representing five Nuu-chah-nulth bands, and the Tla’amin Final Agreement, effective in 2016. Complicating matters, there are two additional self-government agreements that serve nearly the same functions as the comprehensive treaties: Westbank First Nation Self-Government Agreement effective in 2005, and shíshálh Nation Self-Government Act, effective as early as 1986. Unlike comprehensive treaties, Westbank’s self-government agreement did not negotiate the band out from the Indian Act, which means that their reserve land is still held in trust by the Crown and not converted to fee simple property. To maneuver around this inconvenience and create conditions for private ownership, the band utilizes a provision within the Indian Act called Certificates of Possession, combined with long-term leases in the form of land allotments, to enable conditions approximating private land ownership that has since created a highly profitable real estate market on reserve land (in 2019, Westbank’s land value was assessed at more than $2 billion, rising 600% in the 14 years since 2005). For its part, shíshálh (also known as Sechelt) was a very early harbinger for Canada’s Reconciliation era of assimilation: the band negotiated the first self-government agreement with fee simple property two decades before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established in 2007, and a full decade before the exhaustive Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (which was published in 1996 and was compelled by the international crisis caused for Canadian propriety by the Oka Resistance) prefigured the TRC and urged the Canadian government to seek a “new relationship” with Native people, come hell or high water.

For more information, see “History of Treaties in B.C.” (Available at: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/natural-resource-stewardship/consulting-with-first-nations/first-nations-negotiations/about-first-nations-treaty-process/history-of-treaties-in-bc) and “British Columbia: Final Agreements and Related Implementation Matters” (Available at: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100030588/1542730442128).

3 The government of Canada reports that there are about 50 self-government negotiating tables currently underway in the majority of provinces and territories including: Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia and the Northwest Territories. Since self-government agreements result in some of the same assimilatory effects that comprehensive treaties produce, as footnote two explains, further investigation of self-government agreements outside of British Columbia could yield productive insights into a possible tactic for the Native movement that isn’t confined to the particular conditions of BC’s outstanding land claims.